Wars end long before armistices are signed. The end of a war is ultimately a matter of will, of spirit – and the popular will is only reflected hesitantly and reluctantly in the political machinery of peace negotiations.

Although it may seem surprisingly premature to say so, my impression after returning from the Russian front is that the war in Ukraine is over and that the rulers have not yet realized this. In the Kursk salient, at least, I can personally testify to the eerie, almost surreal reversal of spirit between the people of Ukraine and Russia. The moral balance is now firmly in favor of the Ukrainian defenders, and it is far more likely that Russia itself will break up into its constituent republics than that Ukraine will fall prey to its former invaders.

I was in Irpin and Bucha almost three years ago, when they were still smoldering under Russian occupation. The mood then, as we pulled burned bodies with their hands tied from the tree line, was a grim determination forced by tragedy. Evidence of Ukrainian resistance was everywhere: crates of Molotov cocktails on street corners, cursed messages on storefronts, spent shell casings piled behind makeshift barriers against the invaders—all of it pointed unequivocally to a deep-seated determination.

In Russia today, it is completely different: it is a moral vacuum. The civilians of Kursk fled the Ukrainian advance like smoke in the wind, leaving their homes and possessions behind without a sound. I saw exactly one makeshift roadblock, consisting of a few chairs and a rake. Russian civil resistance is (or was) desultory at best. The comparison is stark: despite Russia’s enormous advantages in mass and material, the will to fight is fundamentally absent.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian morale is at the top of the list, bordering on euphoria even. A fiery passion to take the fight to their enemies has infected the front, and operations are being conducted amid a general scrum of units desperate to get in on the action. A sense of Wild West possibility draws in a cast of aggressive fighters, many of whom are eager to engage in their own semi-private pirate operations in the free-for-all. This doesn’t necessarily indicate a lack of Ukrainian command and control, just that the willingness to take on Russia is omnipresent – the Ukrainian forces are like an energetic fighter, barely held in check. The atmosphere is almost celebratory – battle-hardened and combat-ready troops joke and banter at the last gas station before the Russian border, happy and relieved to be free from the gruelling stalemate of the past few months as they race towards the expanding front.

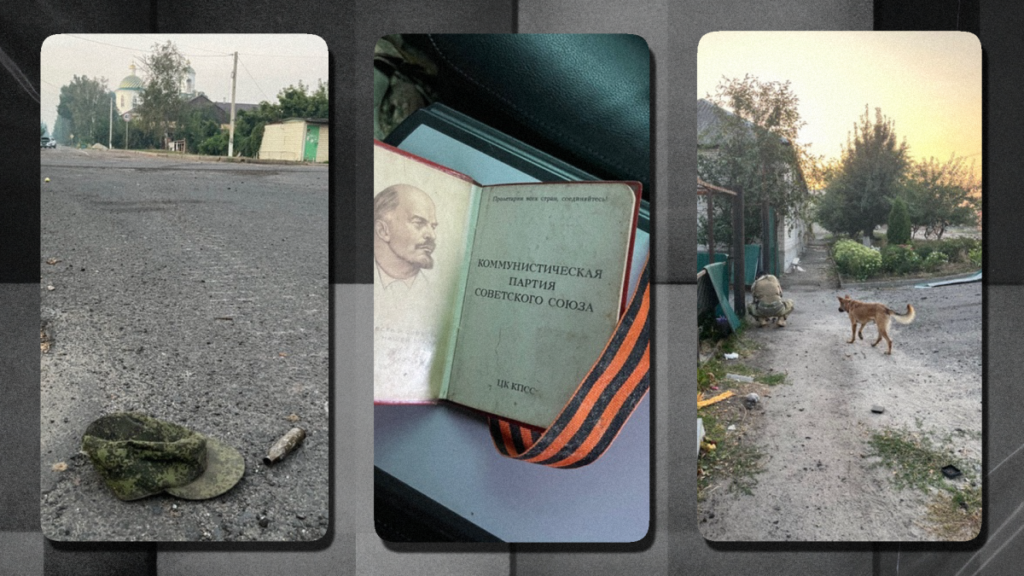

Meanwhile, Russia is quiet. Of the small handful of civilians left in the Kursk area, some interact eagerly with the occupiers, while the rest secretly go about their usual routines. One woman we spoke to turned down an offer of Ukrainian currency (a gift from my daughter), asking bitterly, “And what would I spend my money on?” That?” Dogs and cats wander lost through the streets, while flocks of sheep from the countryside feast on the city’s unharvested fruit trees.

The remaining Russians are engaged in petty, low-level plundering of the homes of their former neighbors. The prevailing feeling is one of poverty—both physical and moral—a kind of bankruptcy of the entire community. A faded plaque on one house proclaimed that a “Veteran of the Great Patriotic War” once lived there, and my Ukrainian comrade remarked on how sadly dilapidated his house was. “Russians are known for mistreating their neighbors,” he said, “but it is the Russians themselves who are mistreated most of all, because they do it to themselves.”

The Ukrainian occupiers, in turn, are too busy storming and slashing these small Russian towns to care about the spoils of war. Moreover, the relatively wealthy Ukrainian troops laugh at the filthy and outdated possessions of their neighbors, constantly amazed at the degree of pervasive shortage. Ukrainian soldiers instead feed the abandoned dogs and then quickly move on to take advantage of the far edges of the active front line.

***

The action in Kursk is a reminder to Westerners that the Russian giant is far from a monolithic, integrated federation. Instead, it is a wavering, demoralized, loosely knit fabric of a nation, held together largely by fear and learned dependence on the state. Separatist sentiment, never entirely extinguished, is growing rapidly in regions such as Chechnya and Karelia and in some 85 other autonomous regions spanning 11 time zones, most of which have long traditions of independence.

Leo Tolstoy famously wrote of the Russian army: “This horde is not an army because it possesses neither any real loyalty to faith, tsar and country – words so often abused! – nor courage, nor military dignity. All it possesses is, on the one hand, passive patience and suppressed discontent, and on the other, cruelty, servility and corruption.” Things have not improved appreciably since then.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has simply run out of moral fiber. It certainly has the resources to engage in a significant amount of sustained chaos. It will, no doubt. But the Ukrainians I have met simply cannot imagine a scenario in which they lose. They are prepared to fight to the last man on the street, and their dedication to freedom is overwhelming. In contrast to the current Russian mood, which seems largely one of confused apathy, Ukrainians have the decisive advantage.

Wars are won in the hearts of a people, not by the rational calculations of military planners. While there is still momentum in the Russian war machine, it is only a matter of time before the reality sets in that Russia’s heart is not in this fight. Whether the war ends in the breakup of its fragile federation or in some half-hearted ceasefire to limit its terrible losses, Russia simply cannot continue. The Kursk offensive, for all its complexities and contradictions, has at least opened a clear window into the popular will of both sides.

The post The war in Ukraine is already over, but Russia doesn’t know it yet first appeared on Reden.com.