There are a surprising number of mass graves surrounding Thabani Dhlamini’s home in southwestern Zimbabwe.

One identified by the BBC is near a primary school toilet block in Salankomo village in Tsholotsho district, where teachers were killed and dumped in the 1980s.

In another grave, a stone’s throw from Mr Dhlamini’s home, 22 relatives and neighbours are buried in two graves – all killed by the Zimbabwean military under the command of then-leader Robert Mugabe.

Mr Dhlamini was only 10 years old at the time, but the memories of this event are still vivid for the frail, gentle farmer.

“We couldn’t talk about it and we were scared to talk about it,” the 51-year-old told the BBC.

They all fell victim to ethnic killings between 1983 and 1987, when Mugabe unleashed the North Korean-trained Five Brigade on strongholds of Joshua Nkomohis arch-rival.

Some describe what followed as genocide. It is not known how many people died – some estimates put the number at over 20,000.

Nkomo was a veteran freedom fighter from the southwestern province of Matabeleland who, more than two decades after his death, is still affectionately referred to as ‘Father Zimbabwe’.

The two men had a troubled relationship during the long struggle for independence against white minority rule: Nkomo came from Zimbabwe’s Ndebele minority and Mugabe from the country’s Shona majority.

They fell out two years after independence in 1980, when Mugabe dismissed Nkomo from the coalition government and accused his party of plotting a coup.

Operation Gukurahundi was launched. The government at the time called it a counter-insurgency mission to root out dissidents who were attacking civilians.

“Gukurahundi” means “cleansing rain” in the Shona language.

The elite troops targeted the Ndebele ethnic group from the Matabeleland and Midlands provinces, and the killings laid the foundation for ongoing ethnic tensions.

Mugabe ruled for another three decades, but only after being deposed by his former deputy Emmerson Mnangagwa it seemed that Gukurahundi would be rightly confronted, even though he was also accused of involvement.

Mr Mnangagwa made a point of raising the issue of reconciliation, given criticism over the way various initiatives to facilitate exhumations and reburials had failed.

Yet it has taken seven years for President Mnangagwa to establish the Gukurahundi Community Engagement Programme. Following Sunday’s launch, a series of community-level hearings will be held where survivors can air their grievances.

Mr Dhlamini said he would participate in the hearings.

“I want to free myself from what I saw, I need to express what I felt,” he said, beating his chest.

In 1983, he and a group of boys from his village witnessed soldiers luring 22 women, including his mother, into a hut and then setting it on fire.

When the women broke down the door to escape the flames, they were mowed down by the soldiers with their guns before they could escape.

Mr Dhlamini’s mother was the only survivor, who managed to hide along the side of a nearby grain hut.

The soldiers then ordered the older boys in the frightened group watching nearby to carry the bullet-riddled bodies of the women into the smoking hut and into another hut next door.

Mr Dhlamini’s 14-year-old friend, Lotshe Moyo, was one of them. Because he was wearing a badge in support of Nkomo, he too was sent inside. He was shot and both huts were burned to ashes.

Today, their remains still lie in the ruins—an overgrown area surrounded by a chain-link fence and many crosses. A whitewashed brick wall is inscribed with the names of the dead.

“When we started talking about it, my memory came back and it was like it happened today. It made me feel like I could cry,” said Mr Dhlamini, who added that his mother was so traumatised that she had never been able to live in the village.

Victims and relatives are divided over whether the new government initiative will bring healing and change their fate.

In the neighboring village of Silonkwe, 77-year-old Julia Mlilo shuffles slowly toward us. She can barely walk now, but she remembers every detail of what happened on February 24, 1983.

When she heard gunshots, she dropped her hoe in the field where she was working and fled into the bushes with her husband and children.

When they emerged, her father and more than twenty of her husband’s relatives had been severely beaten and burned, many beyond recognition.

“Only the heads were identifiable,” she said.

They collected the remains in a tin tub, which was used for bathing, and buried them in a nearby pit.

The site where they were slaughtered and the area where they were buried, adjacent to a field of agricultural crops, are now marked with reflective white and red crosses.

“I have not forgiven them, I don’t know what would make me forgive. When I see soldiers, I feel the pain and I start shaking,” Ms Mlilo told the BBC.

“I don’t trust the process because it is done by the government, but I will participate in it,” she said.

Although Gukurahundi is over, many believe they are still being punished.

Tsholotsho, like many parts of Matabeleland, remains a desolate and deserted area with little to no infrastructure and very little development in the last 40 years.

Since the 1980s, the findings of various commissions of inquiry into the atrocities have never been made public.

During the Mugabe era, a program was started to provide identity documents to children whose parents had died or disappeared, and this program continues today.

However, previous public hearings and excavation programs have stalled.

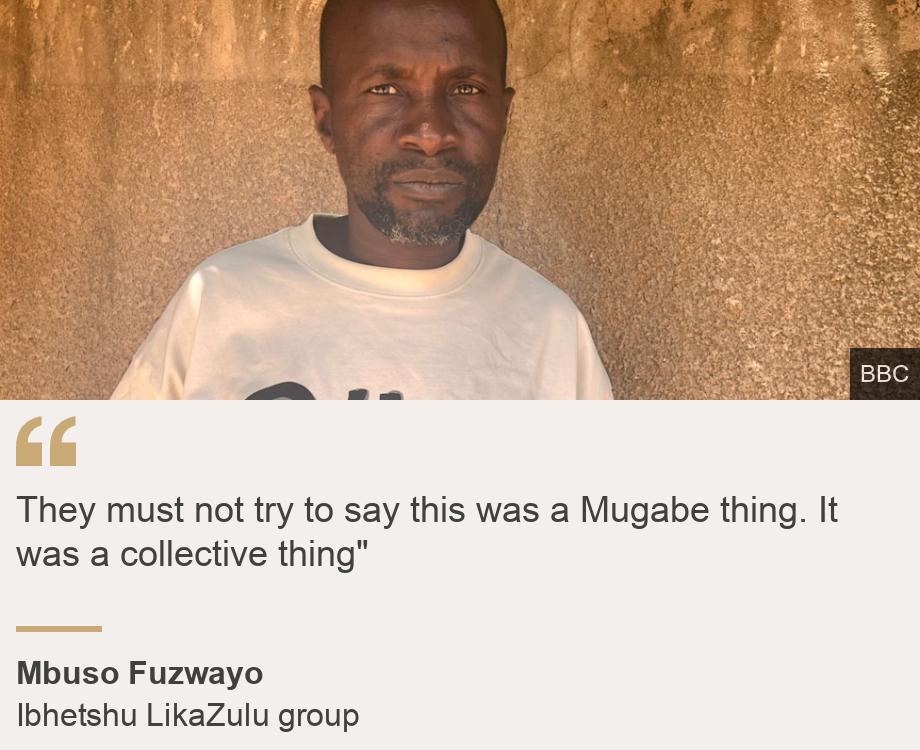

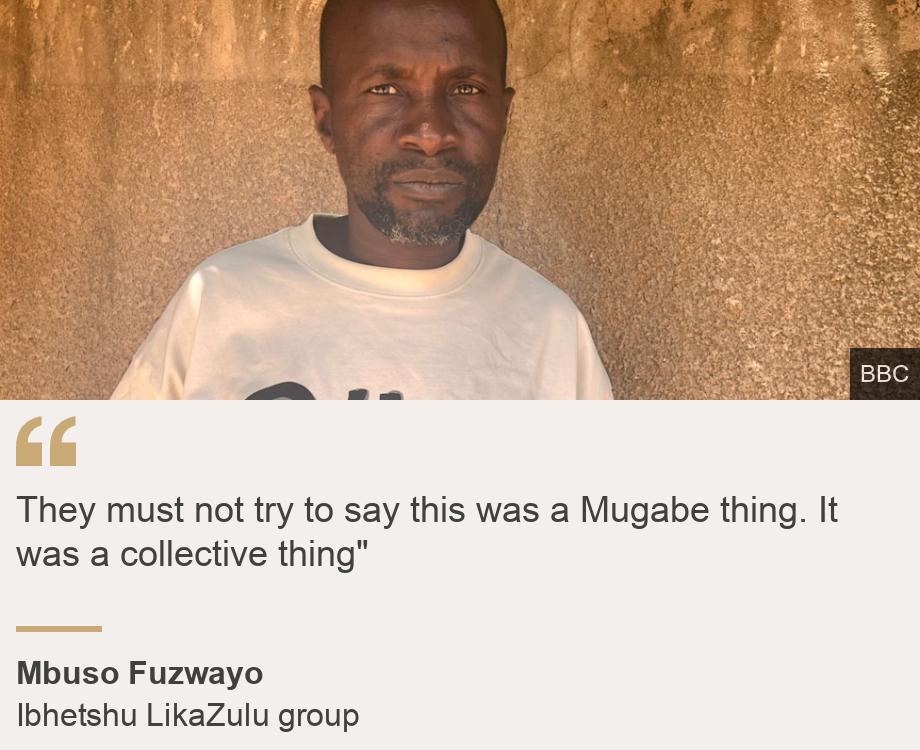

In Bulawayo, the capital of Matabeleland, Mbuso Fuzwayo of the local activist group Ibhetshu LikaZulu spoke to the BBC as he collected a metal plaque commemorating the victims of Silonkwe.

Several plaques the group had commissioned have been stolen or destroyed, a sign that Zimbabwe is still not ready to face its past, he said.

The country has a long history of human rights violations and impunity, dating back to white minority rule when it was called Rhodesia.

“We have a lot of violations against the people. What happened during the liberation struggle is that no one was brought to justice,” Mr Fuzwayo said.

“After the genocide, no one was brought to justice,” he said, referring to Gukurahundi.

“What we are saying is that once justice is done, people will start respecting other people’s rights.”

The suspicions and doubts about the latest process pose a major obstacle for President Mnangagwa, who presents himself as an honest broker with a genuine desire to reunite Zimbabwe and put the past right.

He was Minister of State Security at the time of the massacres, which explains the suspicion towards him in the southwest.

Some of that strong opposition comes from the traditional leaders who will lead the hearings.

Northern Gwanda Chief Khulumani Mathema believes the process is fundamentally flawed.

“It has to be a national issue that focuses on best international practice, which is how genocide is dealt with around the world,” he told the BBC.

Everyone in the region was affected by the atrocities and has a story to tell. As a young boy, the chief was beaten up by soldiers.

“We have countries that have gone through genocide. We have Rwanda, we have Germany, but we want to reinvent the wheel, which I don’t think is feasible,” he said.

“No genocide has ever been fully resolved while the perpetrators are still in power.”

Mr Fuzwayo, whose grandfather was reportedly kidnapped and never heard from again during the massacres, agrees.

“They should not try to say this was a Mugabe thing. It was a collective thing. The main perpetrator may be dead, that’s Mugabe – but Emerson Mnangagwa remains in Mugabe’s absence,” the 48-year-old said.

Despite the constant accusations, Mnangagwa has consistently denied that he played an active role in Gukurahundi, and successive governments have rejected allegations that the operation amounted to genocide.

According to Chief Mathema, the communities’ priority is to exhume and identify the bodies in the mass graves and to provide a space for families to properly mourn their relatives.

But he believes the government has one more piece of the puzzle to complete: telling the truth about what happened and where the missing people are.

This new investigation will test the sincerity of President Mnangagwa – will the hearings hear the perpetrators? Will they open up and give answers to the survivors? Will the findings of previous investigations now be made public?

“To this day we don’t know why the people were killed – what the motive was,” Mr Fuzwayo said.

“And they don’t want to talk about it, and I still believe they have a lot to hide.”

You may also be interested in:

Go to BBCAfrica.com for more news from the African continent.

follow us on twitter @BBCAfricaon Facebook on BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica

BBC Africa Podcasts