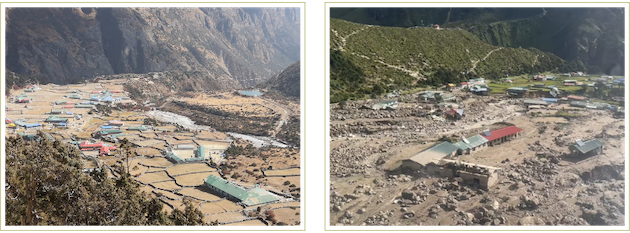

KATHMANDU, Sep 10 (IPS) – Small glacial lakes can wreak havoc, impacting the livelihoods of entire communities. This is the harsh reality facing the community of Thame village in Nepal’s Mount Everest region as they rebuild after the August 16 disaster.

On that day the Thame was hit by a devastating flooda Sherpa village in the Khumbu region, damaging homes, local businesses, a school, a health facility and the community’s livelihoods.

“Thame is one of the main villages that is important in terms of trekking attraction, and the flood has wiped out the entire village. That will definitely affect our livelihood,” said Pashang Sherpa, “Although I am not from that village, I have been working as a trekking guide for 15 years, and villages like Thame are crucial for us.”

A damage report by the local government (Khumbu Pasang Lhamu Rural Municipality in Solukhumbu district) shows that at least 18 properties were destroyed, including seven houses, five hotels, one school and one health post.

“Given the difficult geographical terrain, reconstruction efforts will be costly, and the local government budget will not be sufficient. Therefore, we appeal for assistance from individuals and institutional sectors,” the rural community stated in a request for assistance.

What exactly happened?

Initially the cause was unclear, but now it is becoming clearer: the village of Thame was hit by a flash flood caused by a glacial lake eruptionThe glacial Lake Thyanbo, upstream of the Thames, broke and floodwater mixed with sediment flowed into the village.

“It was the result of more than one event: melting of ice/snow or an avalanche caused flooding from a glacial lake, which then caused an outburst of water from the lower Thyanbo glacial lake,” he said. Dr. Arun Bhakta ShresthaSenior Climate Change Specialist at ICIMOD. “It’s not that both lakes burst, but rather that the overflow or leakage of water from one lake caused the other lake to burst.”

Several weather-related factors played a role in the lead-up to the flood. Recent rainfall and rising temperatures likely contributed to the melting of ice/snow, which in turn led to the eruption. According to the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM)The area received relatively heavy rainfall in the week prior to the event and temperatures were also relatively high.

“This could have led to melting of ice and snow or an avalanche in the upper part of the lake. The runoff caused erosion, which eventually led to the bursting of the lower part of the lake,” DHM said in a statement.

Experts say this flood is the latest example of the causal impact of climate change and the scale of its impact seen locally. Tenzing Chogyal Sherpa, ICIMOD’s Cryosphere Analyst, who is also a member of the mountain Sherpa community and hails from the Khumbu region, sees this event as both personal and a stark reminder of the climate crisis.

“It was just numbing to see the ancestral homes of Sherpa families in ruins,” he wrote on X (formerly Twitter). “Every disaster tests our resilience, but it also strengthens it. We, the mountain community, will emerge united and determined to protect our homes and way of life. Now, more than ever, we must raise our voices to the global community. Our stories and struggles must be heard.”

Small glacial lakes are also dangerous

According to satellite imagery assessments, the lake was about 0.05 square kilometers in size just hours before the breach. “This lake was not on the list of potentially dangerous lakes that can cause GLOFs, and it was not that big. There are thousands of such lakes,” Shrestha says. “This means that even small lakes can cause huge devastation, and our river corridors are not safe.”

There are several lakes upstream of Thame, and satellite images show that the size of these lakes is constantly growing. However, they are not on the list of Potentially Dangerous Glacial Glacial Lakes (PDGLs) like the nearby Tsho Rolpa. An inventory report on glacial lakes was published in 2020 identified 47 PDGLs in the Koshi, Gandaki and Karnali river basins in Nepal (21 in Nepal), the Tibet Autonomous Region of China (25 in China) and India (one in India).

This report identified other small lakes in the region, but these were not listed as PDGLs; there are over 3,624 lakes in total. The report indicates that there are 2,214 lakes smaller than 0.02 square kilometers and 759 lakes ranging from 0.02 to 0.05 square kilometers.

“Yes, lakes are getting bigger by the day due to melting snow and retreating glaciers. But these small lakes are also dangerous in terms of the destruction they can cause to communities downstream,” Shrestha said.

He argues that it is time to integrate potential hazards into development planning and disaster risk reduction (DRR) mechanisms so that disasters like the one in Thame can be prevented. The Thame flood occurred in the afternoon, allowing local people to escape to safety, which prevented human casualties. But if it had happened at night, the situation could have been much worse.

“We are getting multiple wake-up calls, but we are not awake yet,” Shrestha said. “We need to look at glacial lake events from a watershed perspective, not from the perspective of individual lakes. A multi-hazard preparedness approach is needed to prevent greater destruction, because there are thousands of lakes above communities.”

IPS UN Office Report

Follow @IPSNewsUNBureau

Follow IPS News UN Bureau on Instagram

© Inter Press Service (2024) — All rights reservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service