(Bloomberg) — After three decades of stagnation, one of Japan’s most visible signs of renewal can be seen in a stretch of old cabbage fields on the southernmost main island.

Most read from Bloomberg

Apartment blocks, hotels and car dealerships are springing up like mushrooms at a new semiconductor factory amid farmland in Kumamoto Prefecture, which has easy sea access to China, Taiwan and South Korea. The plant, run by global chip giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., opened this year, and another is planned nearby. Wages and land prices in the area are soaring as demand fuels a growing ecosystem of suppliers and related businesses. As jobs open up, the population is booming.

Within an hour’s drive of the factory, however, the city of Misato presents more familiar scenes of economic distress. Once bustling shopping streets are now lined with shuttered storefronts. The population is about a third of its peak of 24,300 in 1947. In its place are growing numbers of roaming deer and wild boar, prompting locals to protect their crops with nets.

Campaign posters for the long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party line the main road that winds through rice paddies. One reads: “Bringing you the feeling of economic revitalization.”

“I don’t feel it because we farmers barely make ends meet,” said Kazuya Takenaga, 67, as he tended his fields of asparagus and rice. The rising cost of fertilizer, energy and utilities has eroded Takenaga’s income. His two sons have left the city in search of work elsewhere.

The two conflicting images expose the biggest challenge facing whoever the LDP chooses as Japan’s next prime minister in an election on Friday: ensuring a broad and lasting recovery takes place across the country, not just in certain areas.

The fight to do so is one of the main reasons Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is stepping down, despite Japan’s economic gains. Nine candidates are vying to replace him as leader of the LDP, which has ruled Japan for several years since the 1950s and is almost certain to win a general election that must be held within a year, in no small part because the country’s opposition parties are weak and scattered.

During the campaign, LDP leadership candidates have grappled with the problem of rural decline and the incessant flow of people from rural areas to cities like Tokyo. Some say the TSMC example provides a model that should be emulated nationwide. Others emphasize tourism or incentives for businesses and academic institutions to relocate to rural areas. Everyone agrees that more needs to be done to increase birth rates, but few have new or radical ideas.

Unless the recovery is extended, Japan risks becoming firmly entrenched as a two-track economy, with the concentration of money and people among the most extreme in the developed world. Businesses will increasingly struggle to find sufficient labor and services, a phenomenon already evident even in Tokyo and other major cities.

For global investors, Japan is firmly back on the map. The stock market is approaching record highs. Deflation seems to have been overcome. Money is flowing in for deals and investments, and the central bank is no longer experimenting with extreme stimulus. The Bank of Japan expects the economy to continue to grow more than its potential growth rate of as much as 1% per year.

Japan’s leaders are also growing more confident on the world stage. Long shy of displays of hard power, the U.S. ally is rapidly increasing military spending in response to concerns about China and North Korea, and is becoming an influential voice on issues such as support for Ukraine.

Since Japan’s defeat in World War II, a growth spurt in the late 1980s has taken the country from occupied ruin to the world’s second-largest economy, after the United States. In 1992, when Japan’s consumer electronics were still the envy of the world, its gross domestic product per capita surpassed that of the United States by $32,000.

But some three decades later, it’s only $33,000. Over the same period, International Monetary Fund figures show, U.S. GDP per capita has more than tripled to $85,000.

Japan’s population began shrinking more than a decade ago and continues to decline by about 600,000 people each year. Combined with a lack of investment, that rapid depopulation has decimated towns and villages across the country. The door has opened a little to foreigners in recent times, but permanent immigration remains largely a political taboo.

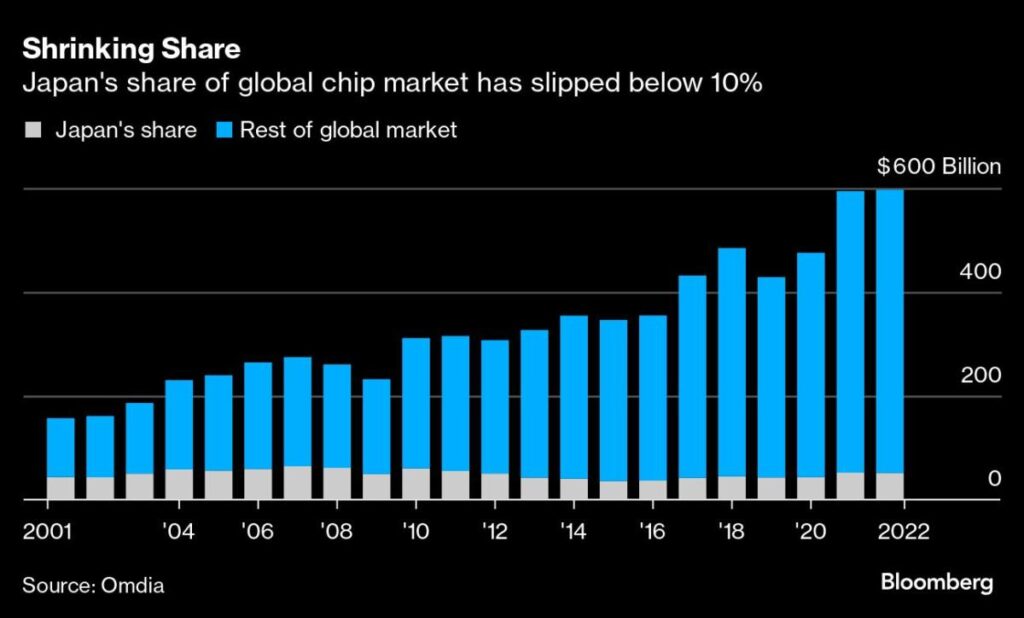

Demographics are only part of the challenge. Japan’s productivity ranks 30th among the 38 members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a club of developed nations. Outside of the auto industry, the slowdown has hurt Japan’s manufacturing sector. While foreign rivals have expanded their global share of chip production, Japan has struggled to keep pace. Through it all, persistent deflation has prompted authorities to make steady 2 percent price growth a key goal to revive the nation.

That long economic standstill explains the current frenzy. Inflation is back as companies give the biggest wage increases in decades, prompting the BOJ to raise interest rates this year for the first time since 2007. The government has also set aside about ¥4 trillion ($28 billion) to revive its chip industry, a strategy aimed at encouraging TSMC and other companies such as Samsung Electronics Co. and Micron Technology Inc. to expand their businesses.

“This is such a good place to be right now,” said Chizuru Watanabe, who moved from another part of the prefecture to take on an administrative role for Japan Material. “You can see that great things are going to happen in the future.”

The city is also strategically important. TSMC’s Kumamoto plant has deepened Japan’s ties with Taiwan, a potential regional flashpoint if China ever seizes the democratically governed island. Those concerns have played a major role in Japan’s moves to increase defense spending from 1% to 2% of GDP by 2028, and in prompting the outgoing Kishida to repeatedly warn that Russia’s war in Ukraine could be a precursor to a similar conflict in Asia.

Some of that money is being spent on anti-ship missiles deployed at a base in Kumamoto that serves as the western regional headquarters for Japan’s military, known as the Ground Self Defense Force. The base is located about halfway between Tokyo and Taiwan’s capital and would likely play a major role if Japan were drawn into a regional war. A recent exhibition basketball game in Kumamoto featuring a Taiwanese professional team showed how ties are deepening with an influx of engineers and factory managers from abroad.

For Kumamoto Governor Takashi Kimura, the city’s economic buzz could help solve the problem of low birth rates and the influx of young people to cities like Tokyo. If people are more excited about the future, he said, they’re more likely to start and stay with families. Moreover, he added, the growth of Kumamoto’s semiconductor supply chain will eventually reach economically vulnerable parts of the prefecture. A local financial group estimated that the chip-making project will generate about $80 billion in economic activity through 2031.

“Our national economy has been closed off for 30 years,” Kimura said in an interview. “But Kumamoto’s opening to Asia shows the way forward for Japan’s economic revival.”

Still, pessimism is high in Nagomi, another city a short drive from the TSMC plant. About 40 percent of the city’s 9,000 residents are 65 or older. Last year, 188 residents died and only 44 babies were born.

Mayor Yoshiyuki Ishihara said he doesn’t expect much to change under a new leader. “Few policies have impressed me, and not many of them have reached the countryside directly,” he said. “I hope they develop policies that make the regions more prosperous.”

Few Japanese residents of small towns like Misato and Nagomi have invested money in markets, private pensions or a stake in M&A activity. The return of inflation is a shock to people who have not seen rising prices for three decades. Imported staples like food and fuel are suddenly more expensive, a fact exacerbated by the weakness of the yen.

During the campaign, candidates for the LDP leadership election have talked more about concerns about the cost of living than they have about the positive aspects of rising prices. Sanae Takaichi, who is rising in the polls, has called for more income support for the most vulnerable in society. Another leading candidate, Shinjiro Koizumi, lamented the loss of national economic champions.

“To put it bluntly, Japan is in decline,” Koizumi said earlier this month during an LDP leadership debate in Tokyo.

“The high growth of the postwar years was led by companies like Honda and Sony,” he said. “They started at the city level and conquered the world. But in the last 30 years, no company of that kind has emerged.”

Yet the Japanese public’s overarching desire for stability limits the scope for drastic policy changes, just as it enables the LDP to maintain its grip on power. Opposition parties have always struggled to offer voters an attractive alternative, and any attractive policy proposals they come up with are often quickly adopted by the LDP.

Until now, Japanese politicians from all sides have failed to offer direct solutions to persistent structural problems such as population decline, said Hideo Kumano, a former BOJ official who is now an economist at the Dai-Ichi Life Research Institute. The TSMC plant in Kumamoto is good for the local economy, he said, but there is a limit to its impact.

“You need a similar economic impact across the country to really revive the national economy,” Kumano said. “And that’s a very big challenge.”

That’s an existential problem for places like Misato, one of Japan’s 744 municipalities at risk of extinction as their populations decline. Kousei Motoyama, 71, president of the city’s Chamber of Commerce and a longtime LDP supporter, said he wants the next prime minister to make sure small towns like Misato aren’t left behind. He hoped the benefits of the TSMC plant would reach the city, but he also wanted more government support for agriculture.

“You can’t continue living here if they don’t improve the economy,” said Motoyama, who owns a small construction company. “Our way of thinking about doing business may be old-fashioned, but we are the people who have supported Japan for a long time.”

Most read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg LP