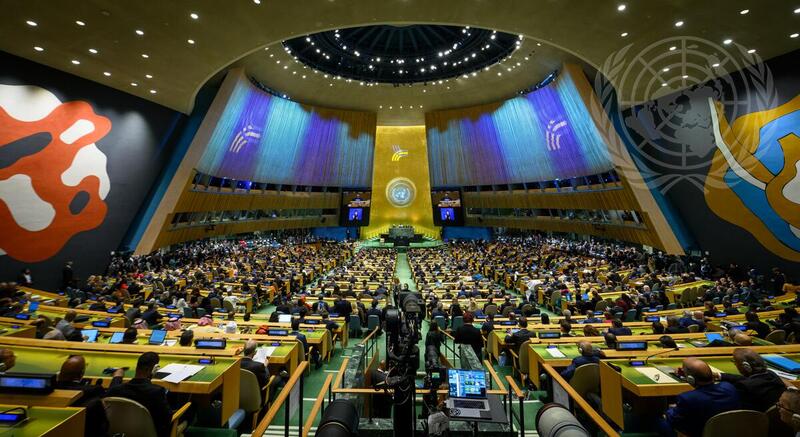

UNITED NATIONS, Sep 30 (IPS) – While most world leaders attending the first UN Summit on the Future, a two-day high-level event at UN Headquarters in New York, aimed to address the most pressing global challenges of the 21st century – agree that the world’s aging multilateral system needs to be modernized, but not everyone agrees on how to achieve that.

“We will not succeed in overcoming our existential challenges if we are not prepared to change the global governance structures that are rooted in the outcome of the Second World War and have become unfit for today’s world,” said Mia Mottley, the Prime Minister of Barbados. during the summit on September 22. “What the world needs now is a reset.”

For the countries that make up the Global South – while not a monolith – the path to reform begins with overhauling the current international financial architecture that has trapped developing countries in an unsustainable cycle of debt. Yet there are doubts whether the blueprint for reform presented in the summit’s non-binding final document, the Pact for the Future, goes far enough to muster the political will needed for change.

Despite months of difficult negotiations and a last-minute amendment submitted by Russia that was rejected, the pact was adopted by consensus on the first day of the summit.

“The Pact for the Future designed an excellent building, but did not leave many instructions for the construction of the building,” said Tim Hirschel-Burns, policy liaison for Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center.

With its 56 action points, the pact, a 42-page document, addresses five areas of global importance: sustainable development and financing, international peace and security, digital cooperation, youth and future generations, and global governance. It also contains two separate appendices, a Global digital compact and a Statement about future generations.

But while Hirschel-Burns describes the language in the pact as “weak” and “fairly vague,” he tells IPS there is still room for some optimism, given that “the pact was signed by leaders of heads of state who represent the peoples of the world. and so “you have a very big mandate” for action, he added. Notably, no leaders from the P5 countries – the United States, Britain, France, China and Russia – spoke at the summit .

One promising action item in the pact calls on signatories to close the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) financing gap – estimated at 4.2 trillion per year – in developing countries. Established in 2015, the SDGs act as a blueprint to eliminate a wide range of global problems, including poverty, hunger and inequality, by 2030.

However, progress on the SDGs has fluctuated for countries drowning in debt and without sustainable options for affordable financing. The latest SDG report estimates that “only 17 percent of SDG targets are on track.” In some cases, progress has stalled or even gone backwards.

Still, Hirschel-Burns says: “Even if the Pact for the Future does not have a clear roadmap for tackling unsustainable debt, the bigger results promised in the pact will not be realized unless meaningful action is taken on debt relief. ”

When accessing finance, global South countries traditionally face much higher interest rates than their neighbors in the West. According to the latest report from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), “Developing regions – in Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean and Africa – are borrowing at rates two to four times higher than those of the United States and six up to twelve times that of the United States. times higher than that of Germany.”

This dynamic has led to developing countries raising $365 billion in external resourcesl debt – money owed to foreign investors, governments and multilateral institutions in 2022.” The report shows that 3.3 billion people “live in countries that spend more on interest payments than on education or health care.” That is almost 40 percent of the total world population of 8 million people.

A separate 2023 report published by Debt Justice, a London-based organization that aims to end unjust debt practices, found that “lower-income countries’ debt burdens reached their highest level since 1998 in 2023.” And foreign debt payments “will average at least 16.3 percent of government revenues for 91 countries in 2023, rising to 16.7 percent in 2024, an increase of more than 150 percent since 2011.”

However, beyond high interest rates and the lack of political will, there are other structural causes for developing countries’ high debt burdens, says Iolanda Fresnillo, policy and advocacy manager of the European Network on Debt and Development (EURODAD), such as unfair trade relations, the technological dependence on China and the Global North, together with the impact of exogenous shocks such as major climate events, pandemics and war.

If countries already in debt don’t have the resources to deal with the impact of a hurricane, an earthquake or a change in oil or other commodity prices, they will have to borrow more, Fresnillo says. So to repay their growing debts, countries have cut spending on health and education and investments in climate adaptation and mitigation, leaving them unprepared for the next big climate event. “We call it the vicious cycle of debt and climate,” she said.

In particular, it is the countries in the global North that emit excess emissions that are driving climate change, but it is the underdeveloped countries in the global South that suffer the consequences that worsen the debt cycle.

“The international community has taken much more ambitious action to tackle this climate crisis,” said Ralph Gonsalves, Prime Minister of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, at the Future Summit on September 22. to go to hell in a handbasket. You know it, and I know it.”

Meanwhile, Fresnillo told IPS that before a multilateral system or blueprint for the future can address the issue of debt reform, a “common framework” must be created. “So when we say the debt architecture needs to be reformed, we mean we need a debt architecture,” because there are no rules when developing countries face a crisis and need to restructure their debt.

“It’s crazy,” Fresnillo said. “If a company goes bankrupt, there are rules that the company must follow to deal with that bankruptcy,” but that does not exist for countries. “It is terribly unfair because those who bear the burden are the people of the country.”

Follow @IPSNewsUNBureau

Follow IPS News UN Bureau on Instagram

© Inter Press Service (2024) — All rights reservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service