(Bloomberg) — Warehouses across China are overflowing with grain as the economic crisis deepens. Farmers around the world are grappling with the prospect of a prolonged economic downturn for one of their biggest customers.

Most read from Bloomberg

The tension on global markets is already visible. French barley exports to China have fallen and the US has yet to sell a full load of new season maize. Wheat farmers in Australia are likely to be nervous as they prepare to harvest their new crop in the coming weeks.

None of this will change anytime soon, and the combination of an ageing population and a cooling economy bodes ill for the future. Traders and farmers will have to adapt to a very different demand outlook. Even if food security concerns keep imports robust in the coming years, the meteoric rise of the past two decades is likely to be over.

“People are becoming more pessimistic about the economy and demand,” said Ivy Li, a commodity market analyst at StoneX in Shanghai. “Importers will be very cautious, buy more slowly and buy more from hand to mouth. The impact of the collapse in confidence is everywhere.”

China’s economic slowdown and the country’s housing woes have dented consumer confidence, causing cash-strapped households to eat less meat and avoid restaurants. It also reduces the amount of farmland needed to feed a large herd of pigs or cook food.

Beijing has already taken steps to protect farmers, asking traders to limit overseas purchases of corn, barley and sorghum — an effort to ease a glut that was exacerbated by a buying spree earlier this year, when traders snapped up cheap overseas shipments that eventually flowed into Chinese ports just as consumption was slowing. The country has also taken steps to reduce the use of soybean meal in animal feed.

Shrinking trade

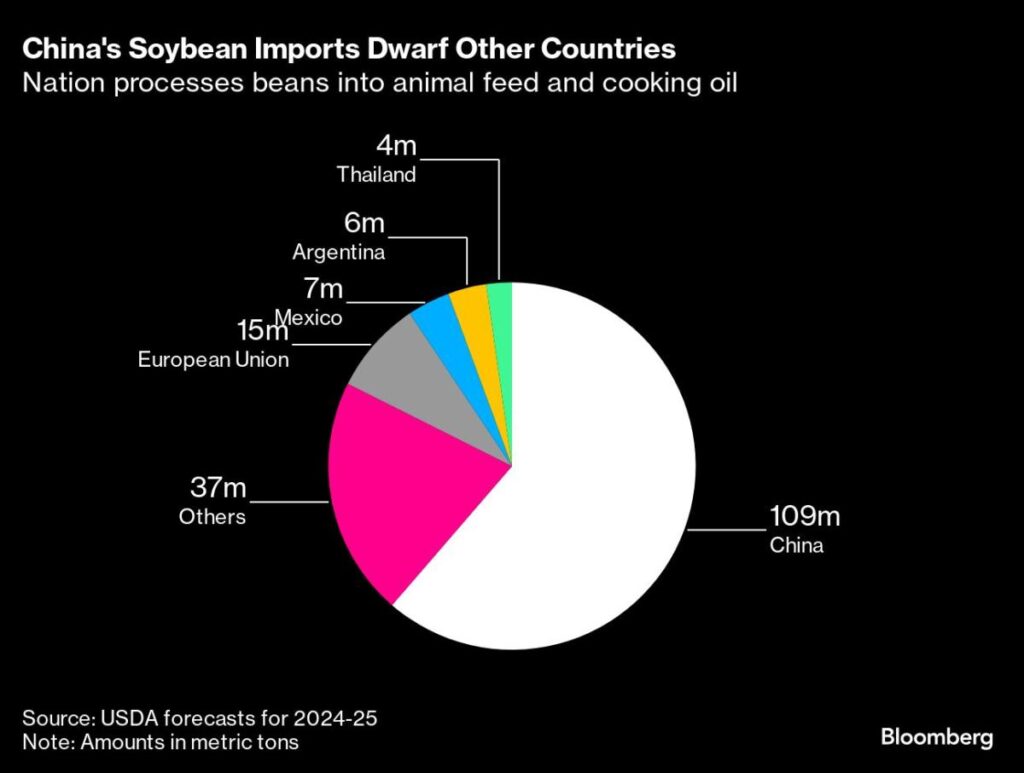

China’s economic boom at the turn of the century transformed the country into a major consumer of commodities from grains to metals and oil, and led resource-rich countries to ramp up production to meet rising demand. China’s domestic agricultural sector is vast, but the need to feed 1.4 billion people has meant that over the years it has become a giant importer of soybeans — and more recently a major buyer of wheat.

For the season that began in September, the U.S. sold just 13,400 tons of corn for delivery to China, compared with more than 564,000 tons a year earlier, according to data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Exports were down 63% over 2023-24. Shipments from Brazil also fell.

Exports of French barley — including malt used to make beer — are down almost 50% this season from the key port of Rouen compared with a year ago. Industry group Intercereales sent a delegation to China to seek clarification from customers about a recent request from authorities to restrict imports.

“We are witnessing a slight freeze in business,” said Philippe Heusele, president of international relations at Intercereales.

Feeding pigs

A key commodity that China will continue to rely heavily on is soybeans, with Brazil and the US the big winners in the trade. Domestic production is still far from meeting needs, even as demand has slowed.

Brazil saw record exports to China earlier this year thanks to cheaper beans, which are used for cooking oil and hog feed. But looking ahead, the U.S. has so far sold less than 5 million tons for delivery in the 2024-25 season — the lowest in 16 years outside the 2018-19 trade war, and down 25% from a year ago.

“Chinese demand is not as strong as in the past,” said Paulo Sousa, president of Cargill Inc. in Brazil. “We are not seeing significant growth as in previous years.”

And local farmers aren’t the only ones feeling the pressure: profits at major hospitality companies in Beijing fell 88% in the first half of the year as consumers became more frugal.

‘Greater control’

The outlook for China’s economy remains bleak, with deflation showing signs of spiraling downward and the country’s annual growth target looking increasingly out of reach this year. Some in China’s agricultural sector are starting to look at the numbers for what imports could look like in 2024-25.

Overseas corn shipments could more than halve to 9-11 million tonnes, while wheat imports could fall to around 7-9 million tonnes (down from 13 million in 2023-24), according to traders in China, who declined to be named because they were not authorized to speak to the media.

Beijing “earlier this year stated their goal of improving incomes for Chinese grain producers and increasing agricultural efficiency, implying that China will impose stricter controls on imports in the future,” said Tanner Ehmke, chief economist for grains and oilseeds at CoBank. “But there is also the clear concern about China’s slowing economy.”

While foreign farmers and traders are likely to see profits shrink, the upside for global consumers is that cheaper grain could ease pressure on food inflation, which has risen since the invasion of Ukraine. The other unknown heading into 2025 is the outcome of the U.S. presidential election in November, which could upend trade flows if the winner takes a hard line against China.

A final question mark is the weather, which could affect plans to reduce overseas purchases. China was forced to feed much of its wheat to animals last year after rain damage, which increased imports.

China has been the largest buyer of Australian wheat in recent years, and is now a producer that some farmers are already looking elsewhere.

Farmer Andrew Weidemann typically ships about a fifth of his grain to China. He expects that volume to halve. “Anything that happens in China is going to have a huge impact on markets elsewhere,” said Weidemann, who runs a 4,000-hectare farm in central Victoria in southeastern Australia.

–With help from Celia Bergin, Nayla Razzouk, Gerson Freitas Jr., Clarice Couto and Isis Almeida.

Most read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg LP