Wu’er Kaixi is still angry when he thinks about the June 4 tragedy that shocked the world 35 years ago, he told dpa during an interview at a teahouse in Taichung, Taiwan, on a sunny day in May.

The 56-year-old prominent Chinese exile was one of the key figures who led tens of thousands of students who protested in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989, demanding democracy and government reforms.

The protest ended in a bloodbath, a subject that remains taboo in China even decades later.

All documents and files about the truth are still kept by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regime.

To this day, images of the person known as “Tank Man” – the man who stood alone in the path of the approaching tanks – remain a symbol of ordinary people’s protest against the authoritarian regime.

He was the man who stood in the way of the tanks sent by the authorities to put down the protests, stopping their progress by staying directly in their path, a standoff that became one of the most iconic images of the events that summer.

“The gunshots were loud,” said Wu’er Kaixi, recalling the night of June 3-4, 1989, when soldiers arrived. The violent crackdown put a bloody end to weeks of peaceful protests led by students calling for political and economic reforms.

“We want a dialogue. We want to have a say. We want to be heard,” he said. The demonstrators demanded that the democratic student movement be recognized and that political elections be held.

Looking at today’s China, under head of state and party leader Xi Jinping, these demands still seem like an impossible dream.

But the problem is not Xi, but the system itself, says the 68-year-old Wu Renhuawho was also one of the demonstrators in Tiananmen Square in 1989.

“If the Communist Party in China does not take the initiative to initiate democratic transformation, it will eventually one day be overthrown by people like the communist regime in the Soviet Union and in Eastern Europe,” Wu said to dpa in a small cafe in China. New Taipei City, near the Taiwanese capital Taipei.

Early hope for an opening

In the 1980s, China’s economic modernization gave rise to hopes for reform. Many people looked at Hu Yaobang, then general secretary of the Communist Party, who worked with reformer Deng Xiaoping. But that democratic opening never came. Hu was deposed in 1987 and died in April 1989.

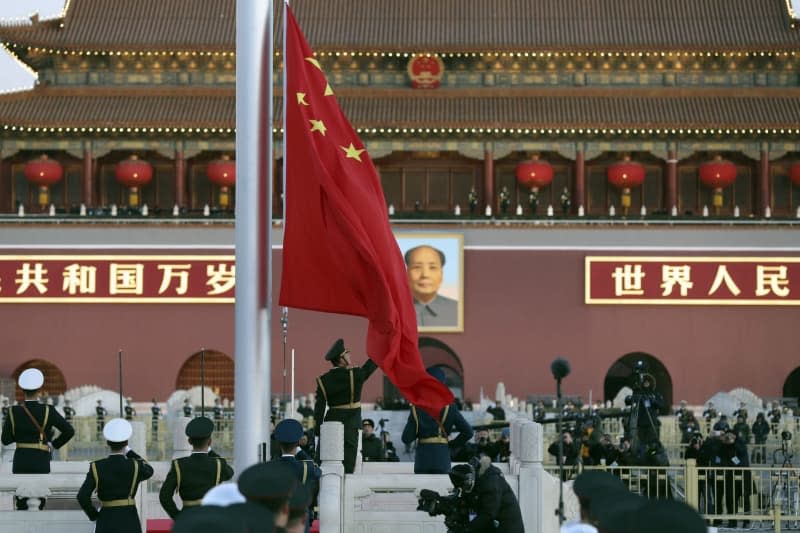

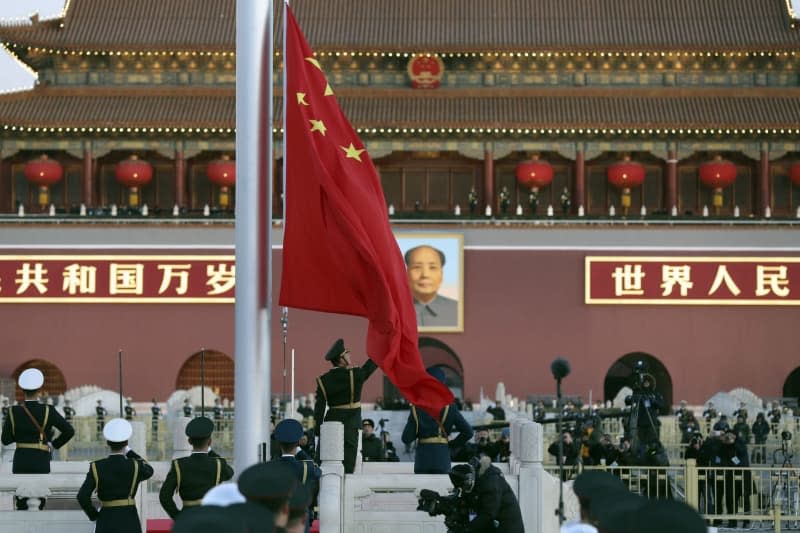

Wuer Kaixi’s memories are still vivid of the Tiananmen Square incidents 35 years ago. The pro-democracy rally took place right in front of the portrait of Mao Zedong, once the communists’ most powerful revolutionary leader, whose photo adorns the entrance to the Forbidden City.

One of the biggest inspirations at the time was the Polish Solidarity Movement, says Wu’er Kaixi, from the union that challenged the government and won elections. “We hoped that a similar situation could arise in Beijing,” he said.

A “bloody scene”

In May 1989, demonstrators underlined their demands by staging a large-scale hunger strike. By then, even Beijing was no longer able to control the protests. On May 15, demonstrators even prevented Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev from appearing on the square, where state guests are usually received with pomp and ceremony.

Shortly afterwards, approximately 1 million people, including workers and citizens, young and old, joined the students to protest together. The Chinese leadership, faced with the demonstrations that took place in front of the world’s press, was humiliated. The party eventually called in the People’s Liberation Army.

“Early in the morning of June 4, 1989, I and about 2,000 students guarded Tiananmen Square until we were driven out by troops,” said Wu, who was teaching at a university at the time. Tanks pursued them as they ran west.

“One of the tanks, number 106, sped away from the rear, killing 11 people on the spot and injuring many more,” Wu said. “The scene was so bloody,” he added.

Escape in an ambulance

Wu’er Kaixi also fled from the square in the heart of Beijing that night “in the last ambulance,” he says. In the same vehicle, a student died with a serious head wound covering his eyes. “Anger is one of the many feelings I had,” he says.

It is still unclear how many people died in the suppression of the peaceful protest, which is officially called just an “incident” in China. Hundreds are believed to have died. Researchers also pointed to a Chinese Red Cross estimate at the time of 2,600 deaths. “The truth will come out one day,” Wu’er Kaixi says with certainty.

Many former protesters left China and now live in exile. This is the only way they can talk about their experiences. “Such a massacre that shocked the world, even 35 years later, the Chinese people are still not allowed to talk about it. I feel very sad,” said Wu.

The meaning of June 4 is well known in China. But the people traded their silence for the prosperity that came with Deng’s reforms and opening. Nowadays, people can enter Tiananmen Square only by reservation and undergo strict bag checks. No commemorations of the massacre are held.

Arrests before Remembrance Day

In Hong Kong, tens of thousands of people turned out for vigils held annually between 1990 and 2019 to commemorate the victims of the 1989 pro-democracy movement.

However, in 2020, Beijing tightened controls there in response to protesters demanding greater democracy. The strict national security law further silenced dissent and made the public commemoration of June 4 impossible.

This year, days before the 35th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, Hong Kong police arrested several people accused by the authority of posting on social media about a “sensitive date,” reported locally as the commemoration of Tiananmen Square on June 4.

In China, efforts to promote democracy are facing increasing repression. Some were hopeful after the 2022 protests, when people took to the streets in many places with white paper against the government’s strict Covid-19 restrictions.

Known as the “White Paper Movement,” it was the largest collective protest calling for political change since 1989, Wu says. Even though the short duration of the protests made them incomparable to those of the 1989 pro-democracy movement, they were still of great value, he said.

The hope for change lives on

The people are still there, says Wu’er Kaixi. “And also the demand for government transparency, for a balance of power and for participation in public affairs.” The question now is how the government will deal with these wishes, he says.

“Our ultimate goal is democracy in China, a multi-party system, freedom of expression and open elections,” said Wu’er Kaixi. While it won’t be easy with Beijing’s fear policy, “pressure always works,” he says.

The world has satisfied China for the past 35 years, but this will not help, says Wu’er Kaixi. “You can be on the side of the tanks or on the side of the Tank Man. There’s nothing in between.’

The regime will eventually collapse, Wu says. ‘From time immemorial until now, there has been no regime that can last forever, especially not such an evil authoritarian regime. It can’t last forever,” he says.